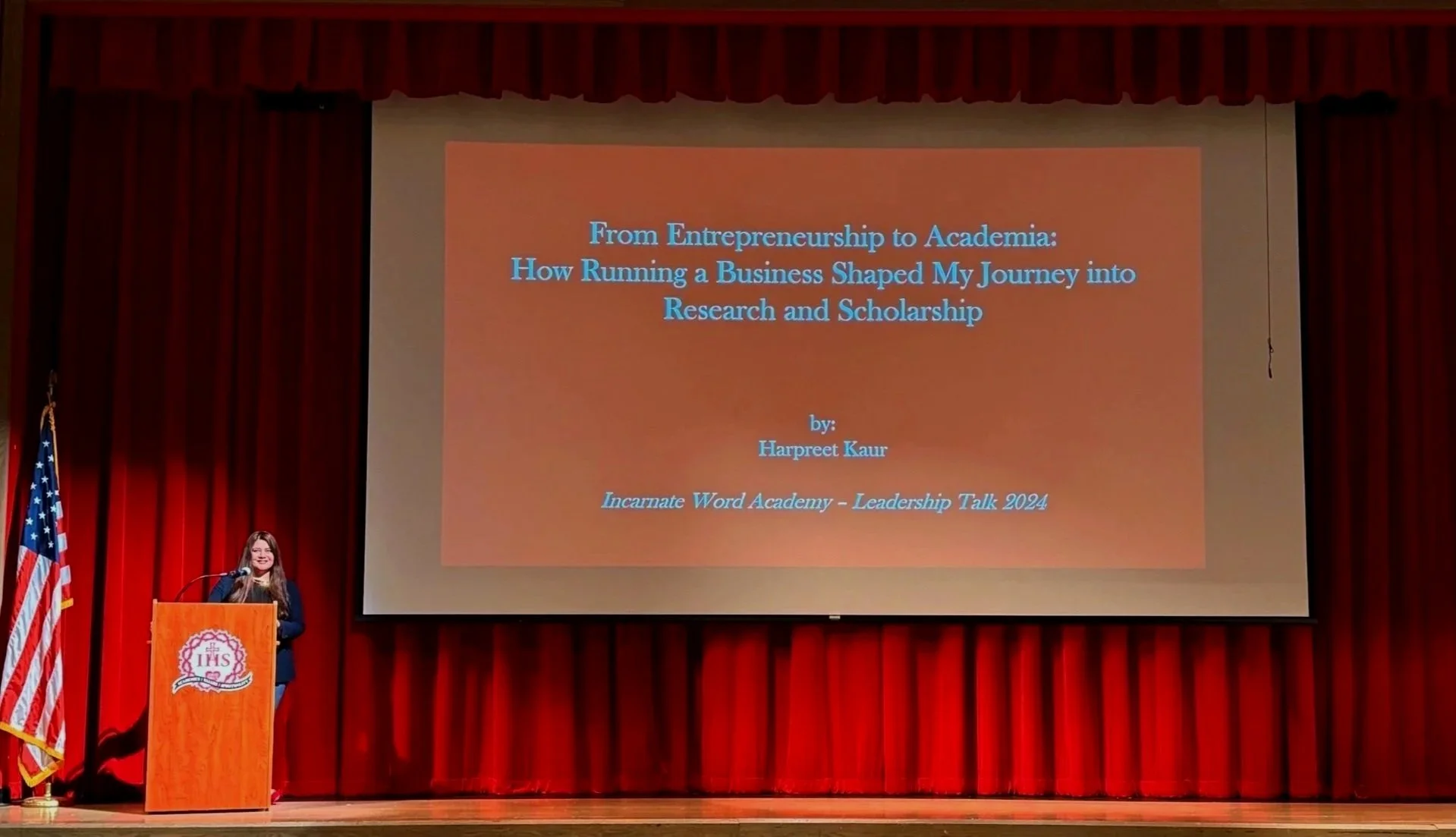

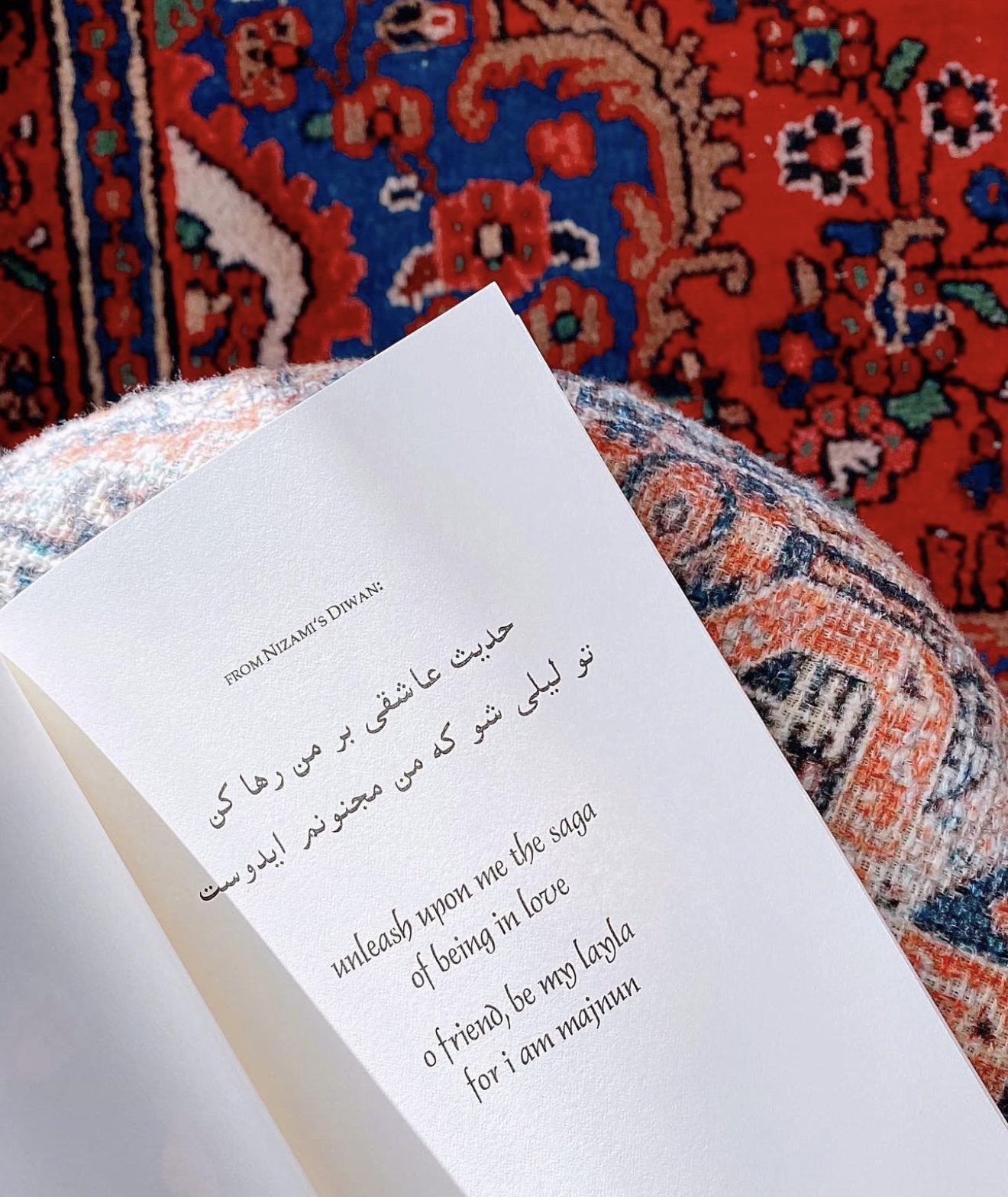

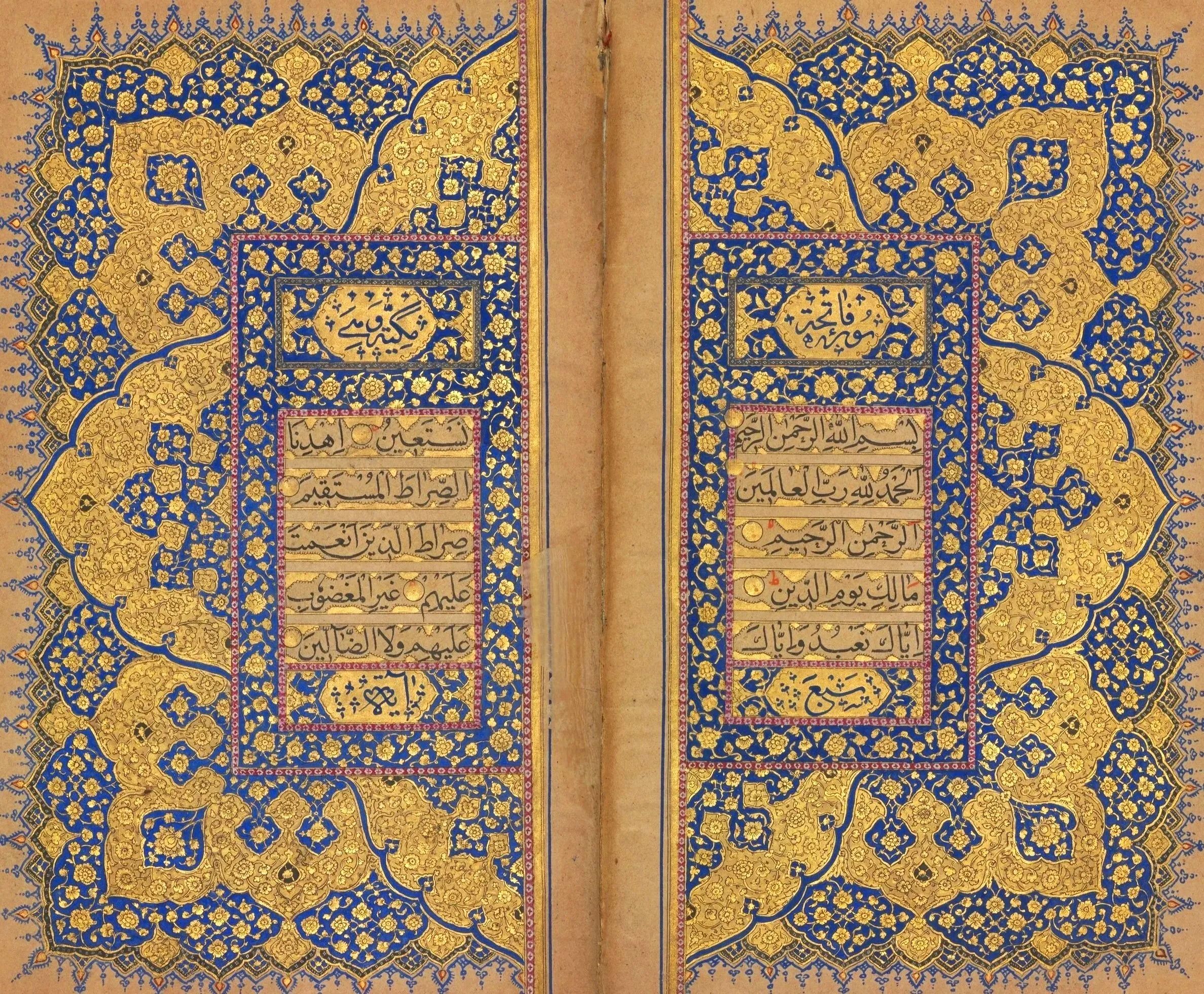

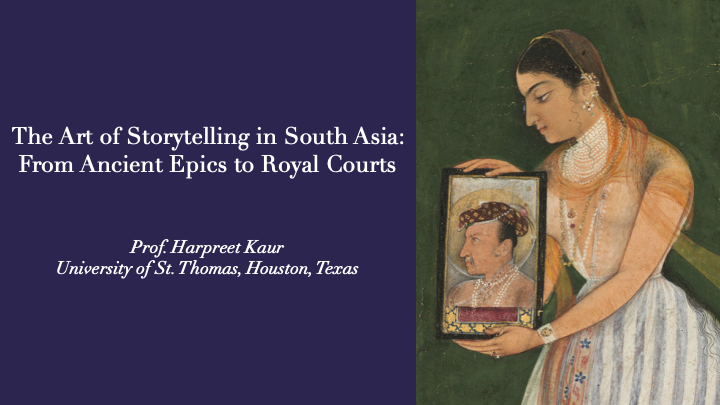

Welcome to The Kitāb Khāna, the digital home for some of my work as a historian of the Islamicate and Persianate worlds. My research explores the art, literary culture, and devotional practices that animated South Asia, Central Asia, and the wider Islamicate sphere. I study the world of the manuscript including its makers, its patrons, its readers and the intellectual and aesthetic conversations that unfolded across courts, shrines, and dispersive networks of scholars.

As an extension of this space, I also imagine a Khānaqāh-i ʿIlm, خانقاهِ علم, a “hermitage of knowledge”, where reading, reflection, teaching, and dialogue come together. If the kitāb khāna is a library or atelier, the khānaqāh-i ʿilm is its inner sanctuary: a space for contemplation, generosity, and the slow work of thinking across traditions.

Together, these ideas shape my approach as a professor. I teach with the conviction that the humanities are living practices, and that to study the world of the book is to encounter people, ideas, and histories that continue to resonate today.

I hope this site offers a glimpse into that world and invites you to enter, explore, and learn alongside it.

MISSION

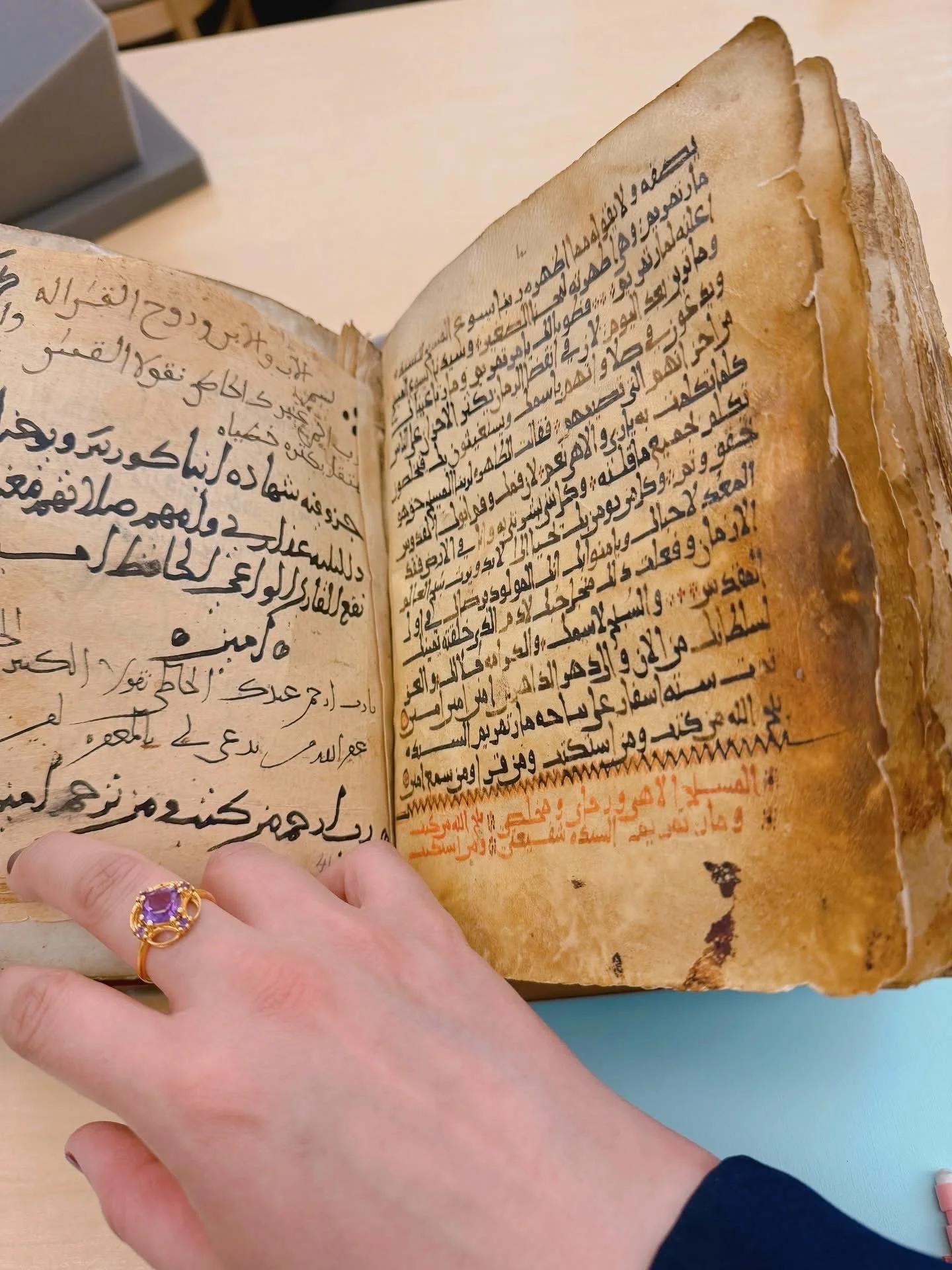

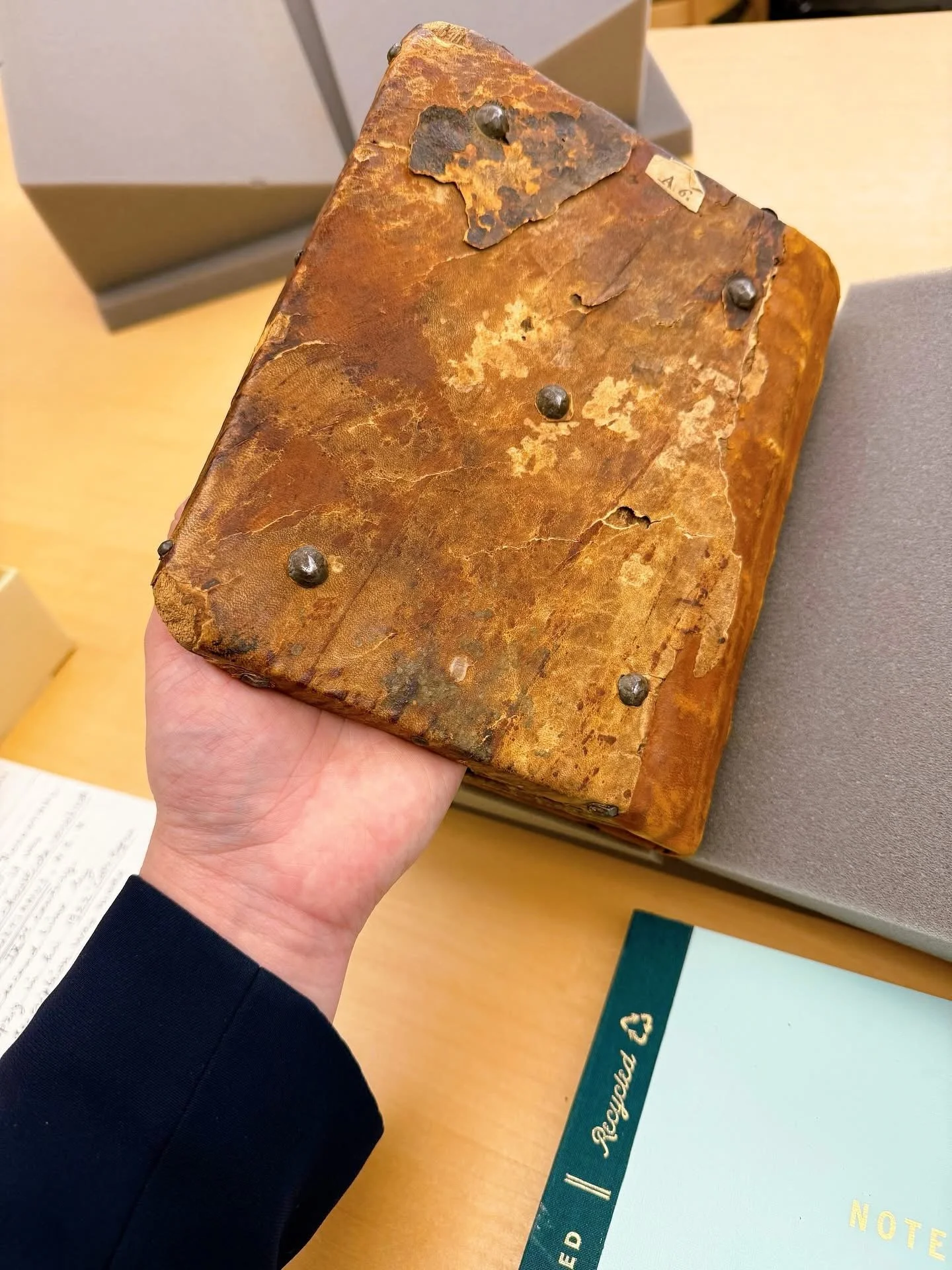

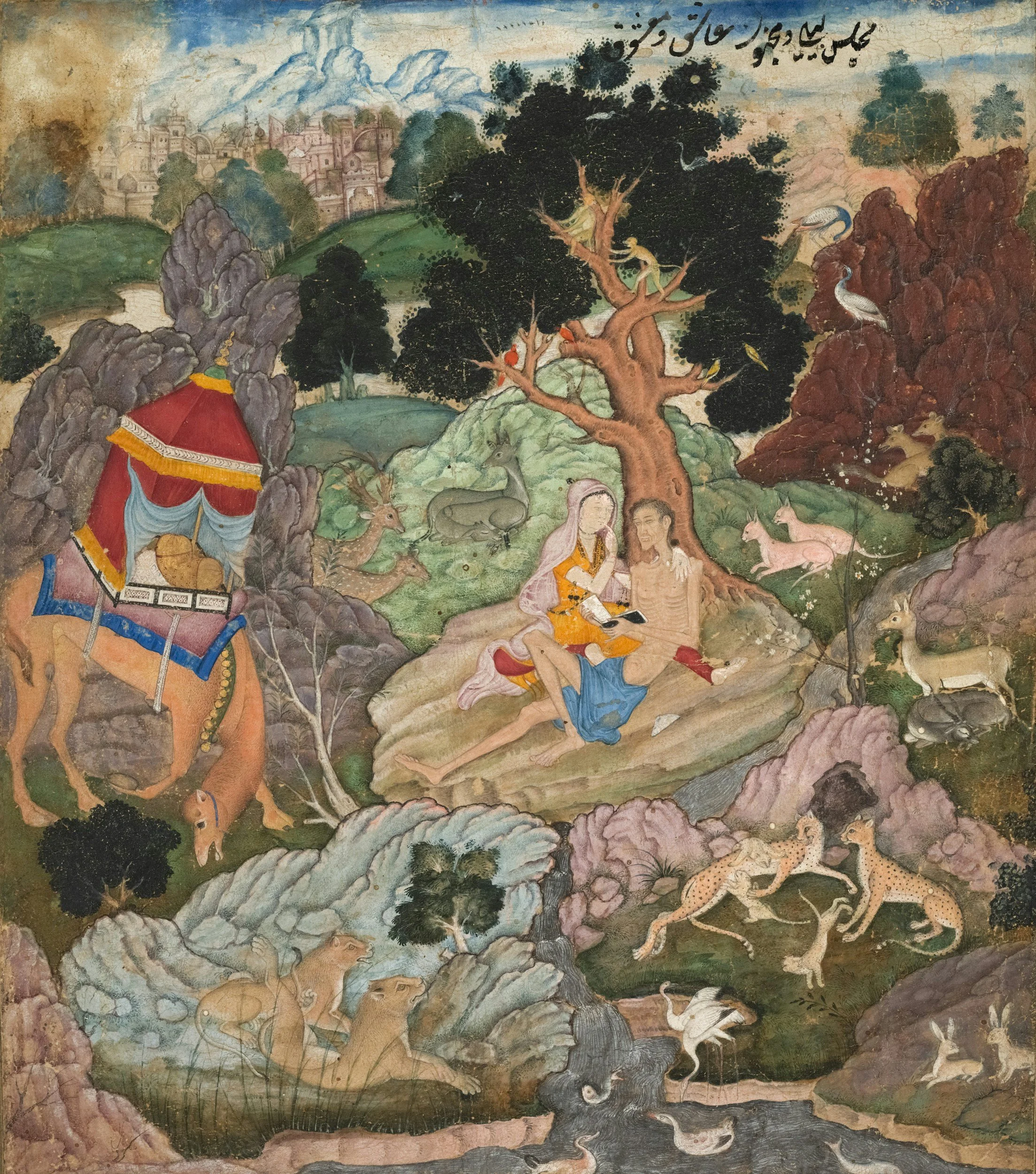

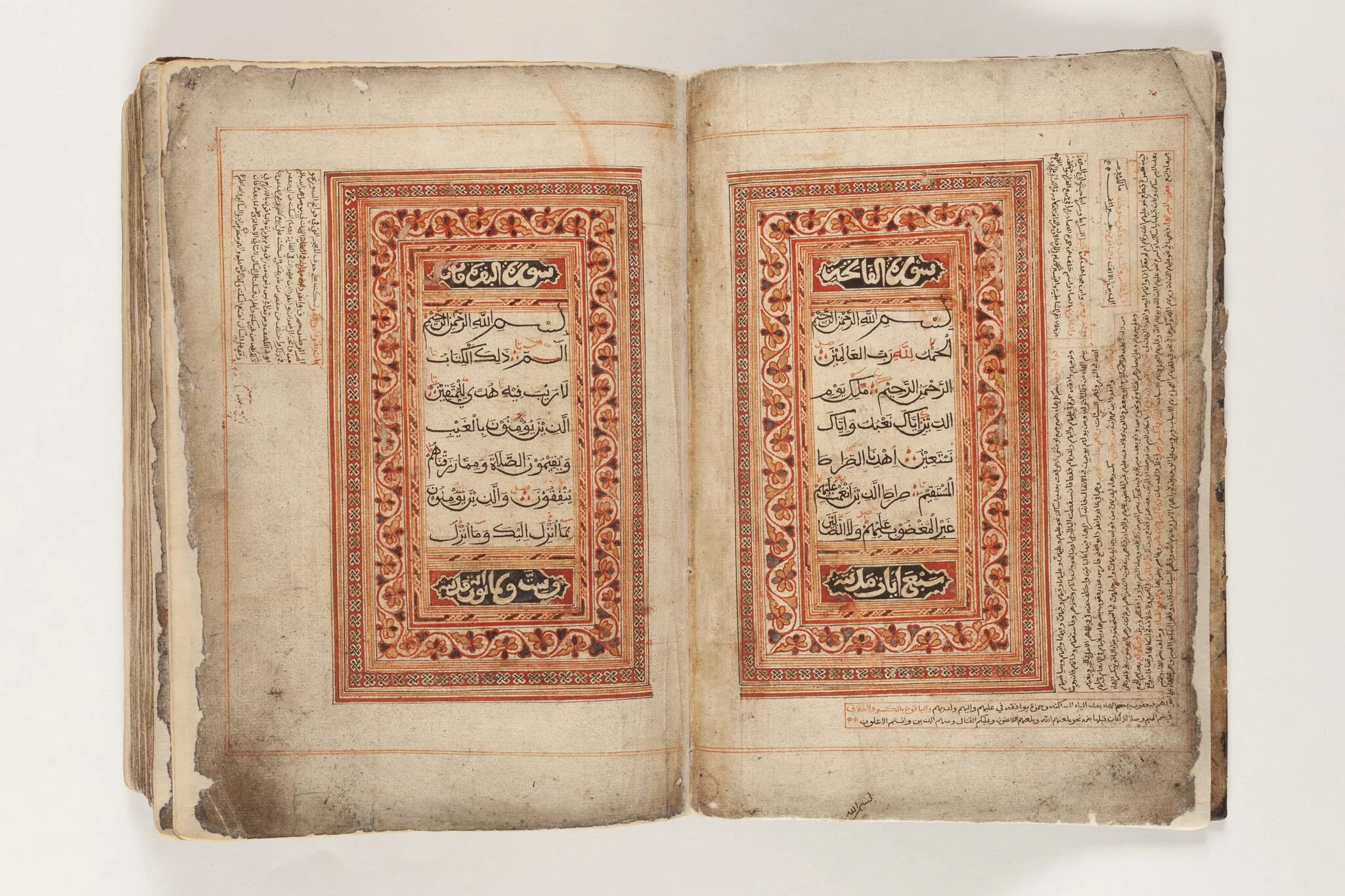

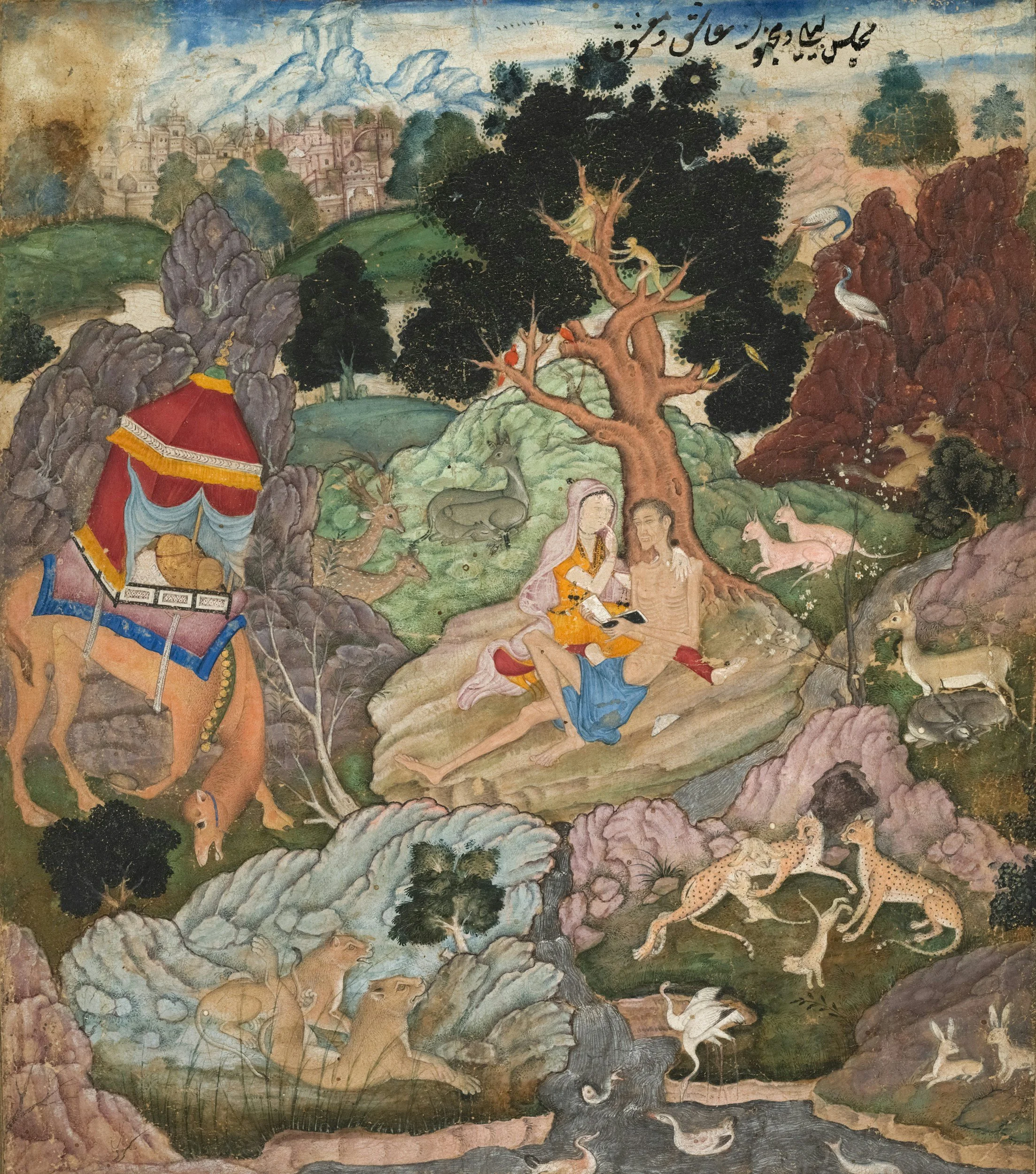

My scholarly and pedagogical mission is to deepen critical understanding of the Islamicate world through the study of its art, manuscripts, and material culture. By supporting inclusive scholarship and public engagement, this work seeks to foster sustained appreciation for the historical, cultural, and intellectual traditions embedded in these objects. Central to this approach is the study of special collections in institutions across the United States and abroad, particularly materials that have remained understudied, in order to broaden the geographical and institutional scope of manuscript scholarship.

SPECIAL COLLECTIONS VISITS

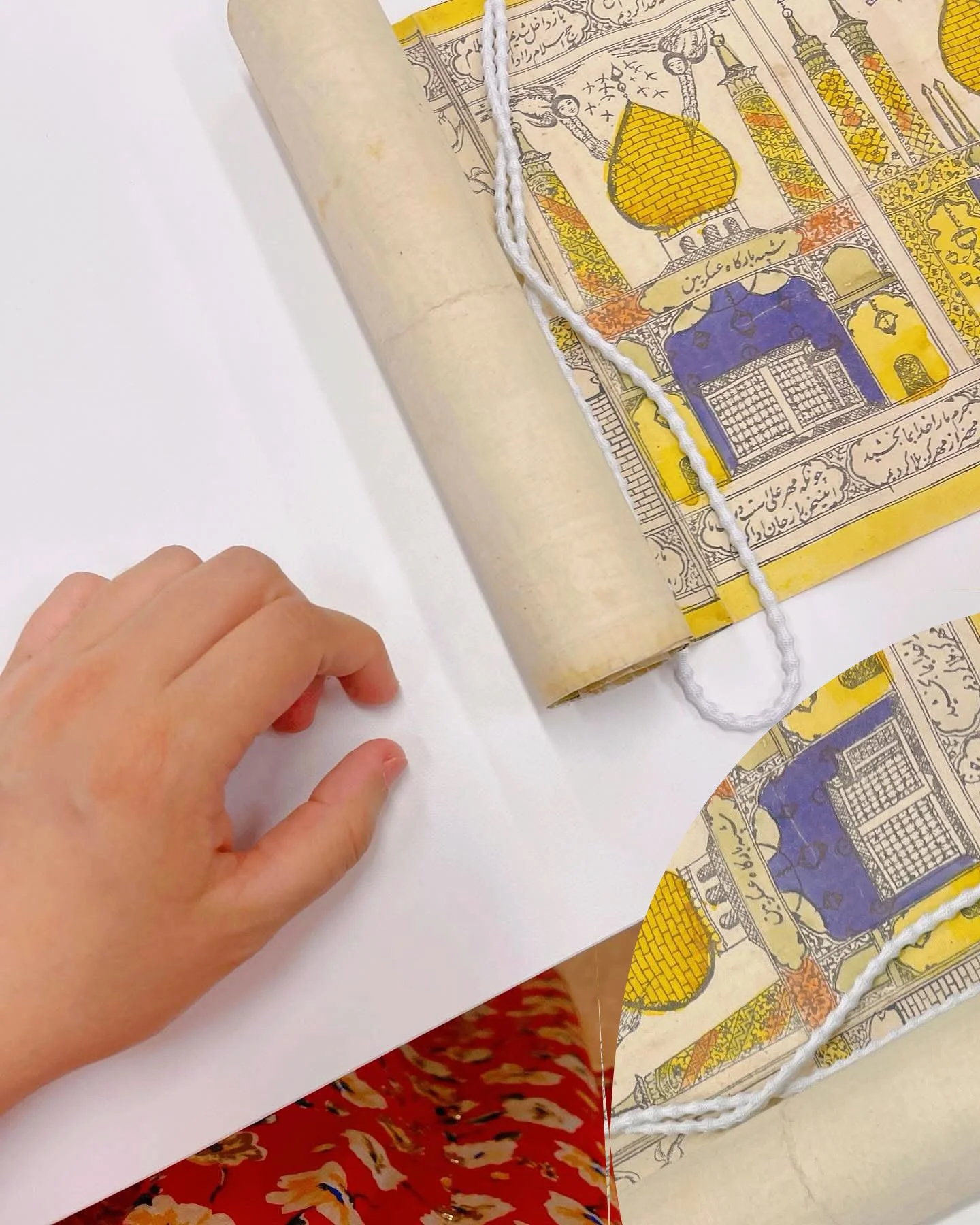

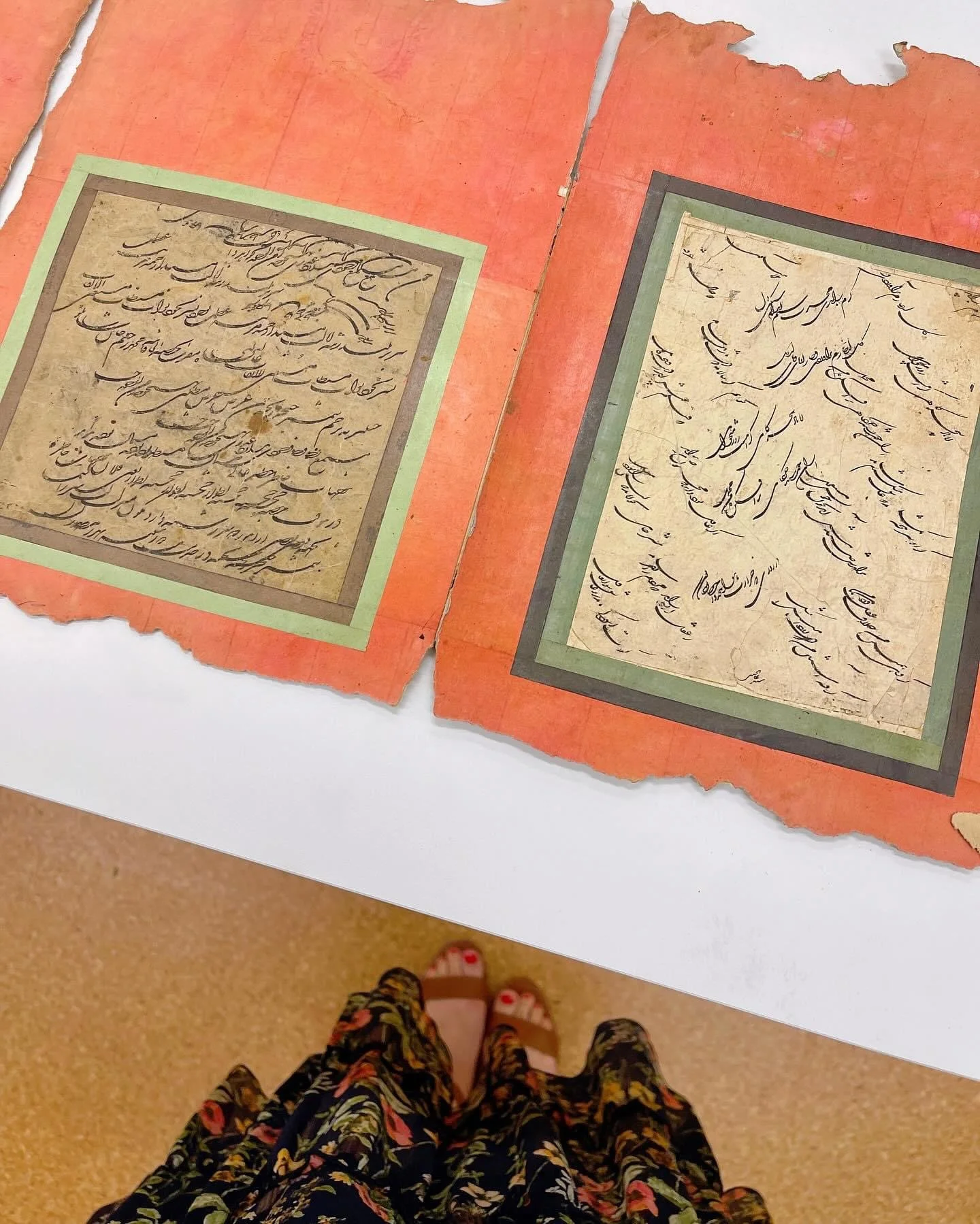

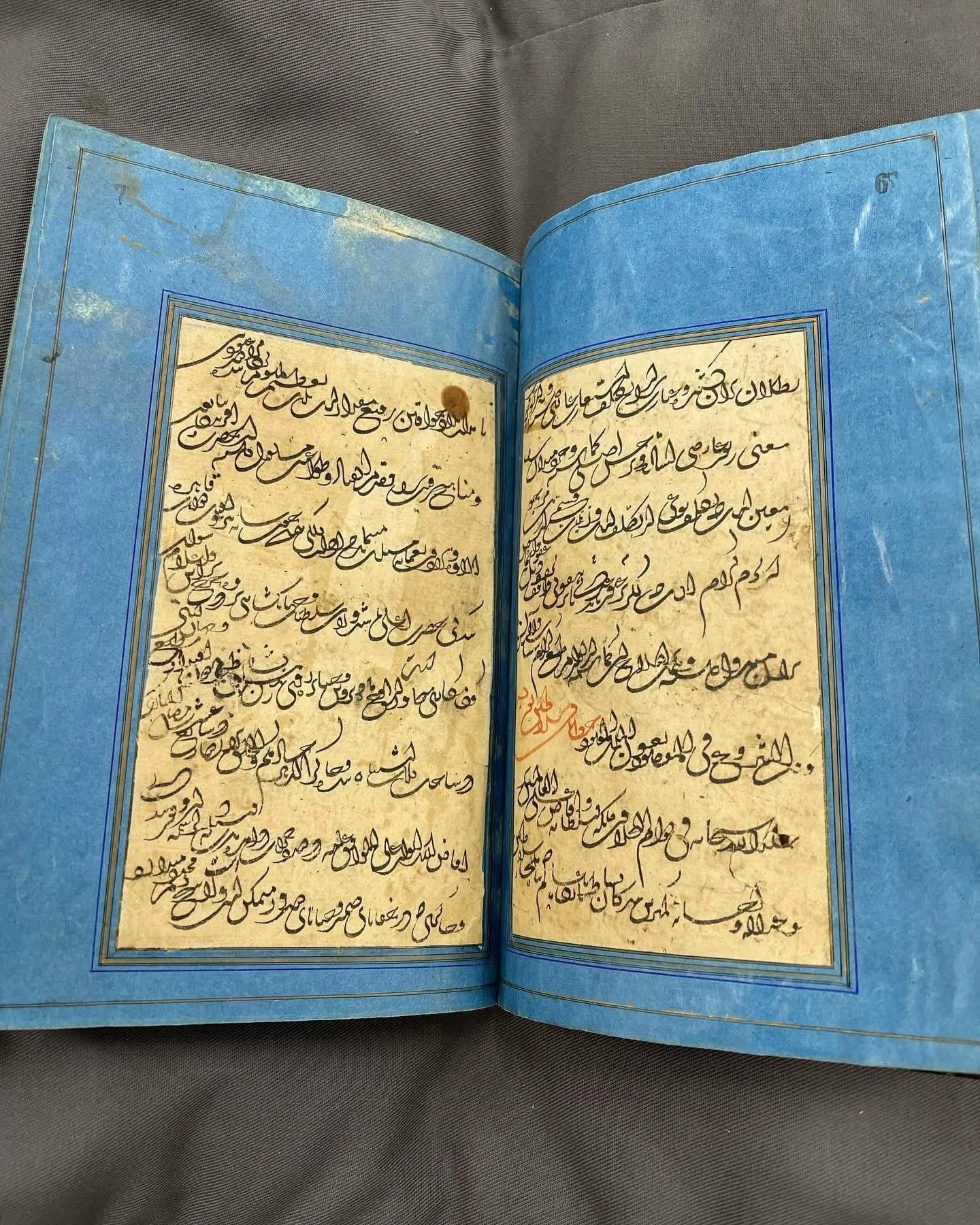

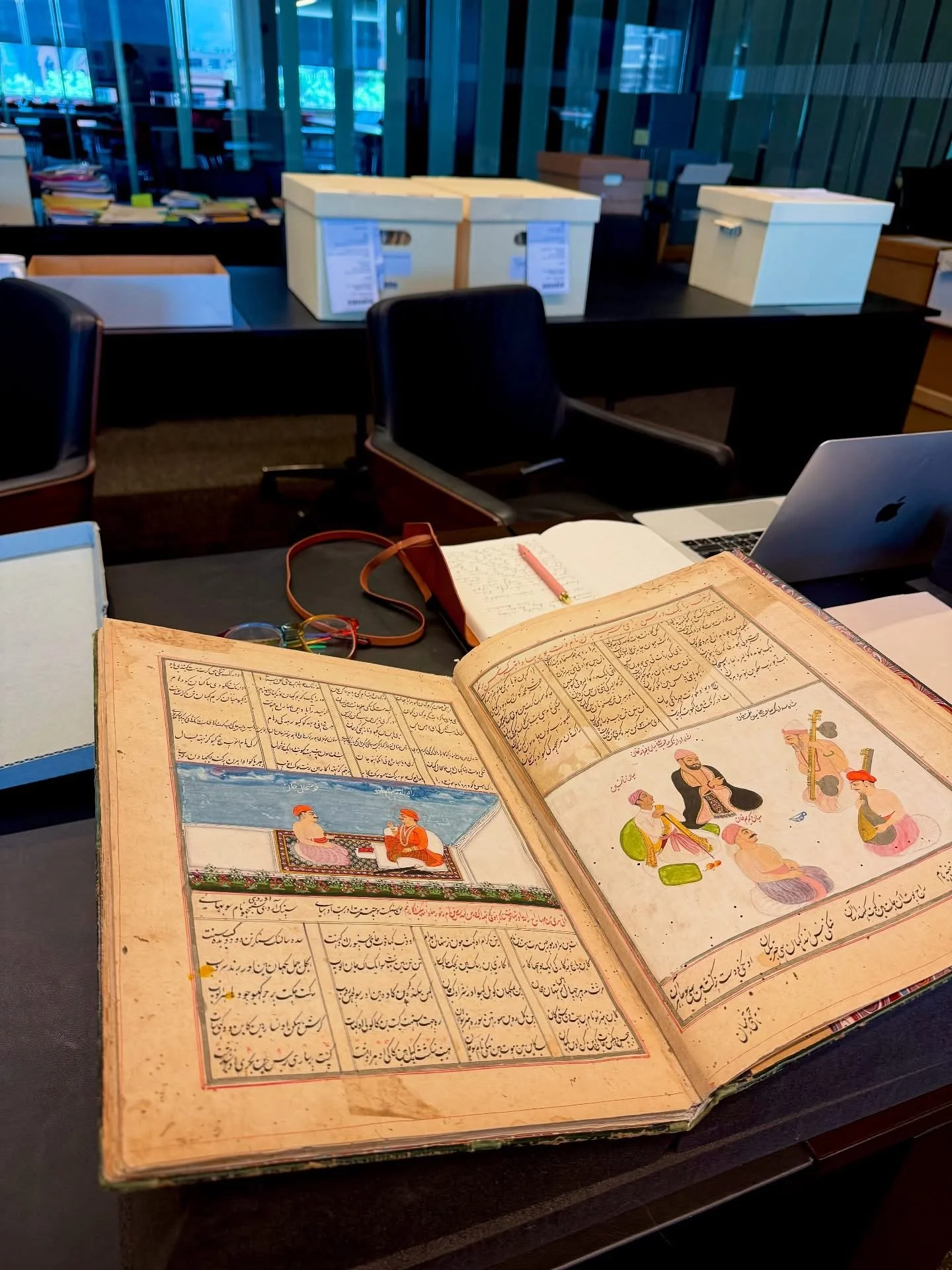

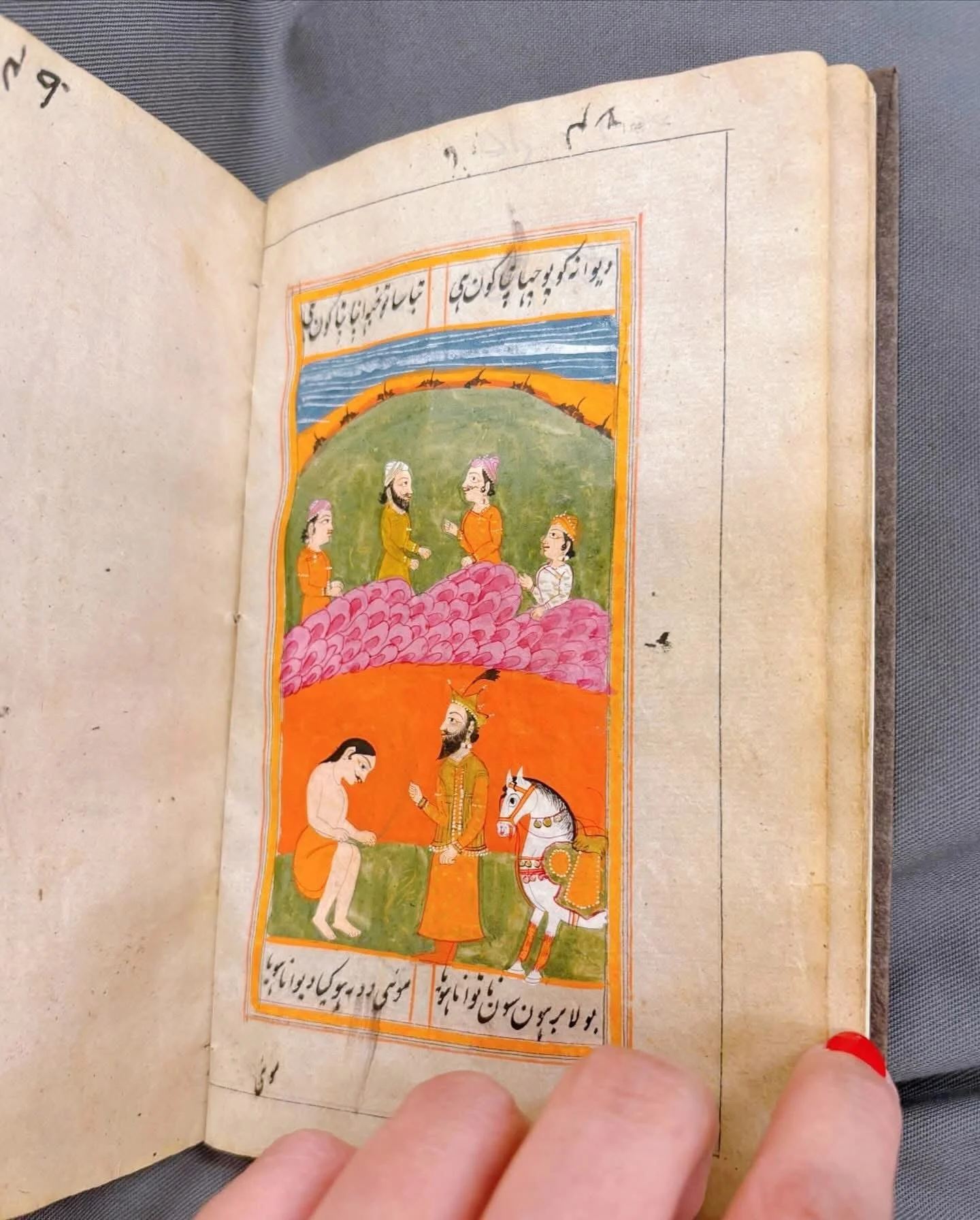

This research is grounded in sustained engagement with special collections and rare book libraries, emphasizing hands-on analysis of manuscripts, codices, and archival materials across South Asian, Persian, and Islamicate traditions.

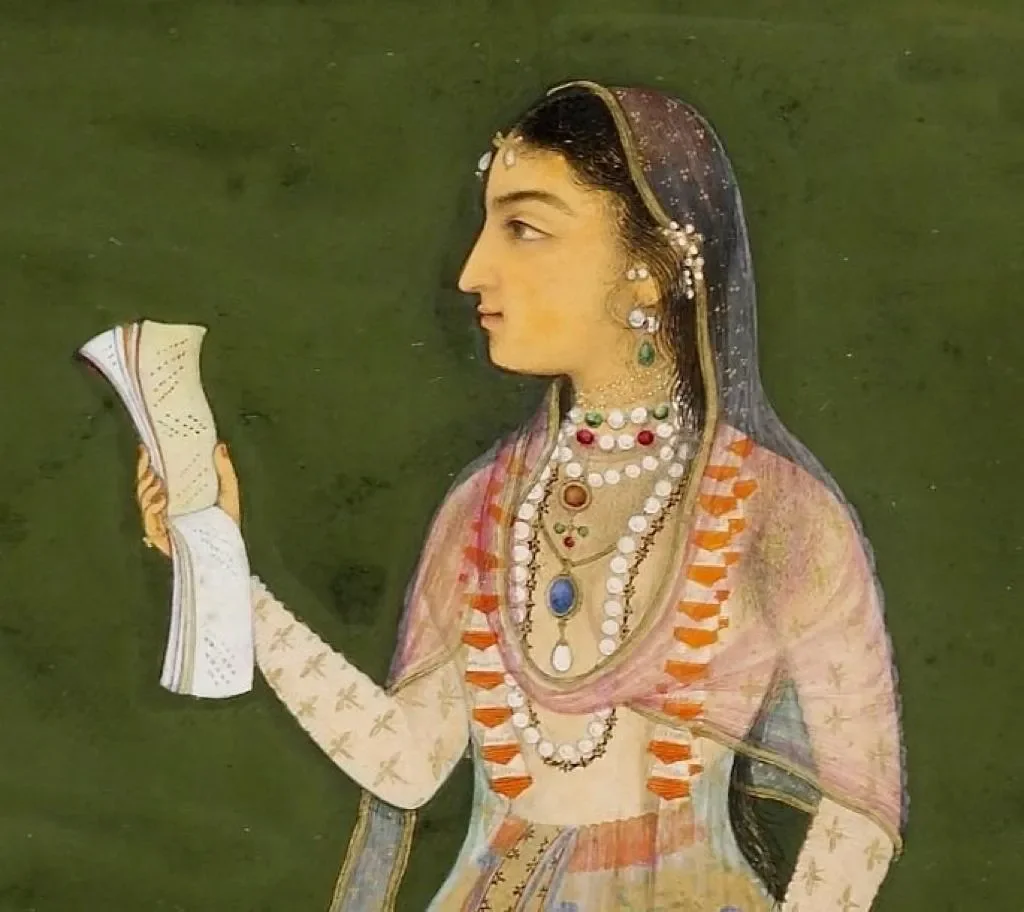

“There had been an order issued, ‘Write down whatever you know of the doings of Firdaus-makani (Babur) and Jannat-ashyani (Humayun). At this time when his Majesty Firdaus-makani passed from this perishable world to the everlasting home, I, this lowly one, was eight years old … However in obedience to the royal command, I set down whatever there is that I have heard and remember.”

- Gulbadan Begum, Humāyūn-nāma, trans. Annette S. Beveridge (London: Royal Asiatic Society, 1902), introduction.

Islamic art first reveals its beauty, then reveals an act of devotion; it waits for its audience with patience.

PERSONAL LIBRARY

“In connection with an account of Kabul, I was shown His Majesty Firdaws-Makani [Babur]’s memoirs. They were entirely in his own blessed handwriting, except for four sections I copied myself. At the end of these sections I penned a sentence in Turkish to show that the four sections were in my writing.

Although I grew up in Hindustan, I am not ignorant of how to speak or write Turkish."

— Jahangirnama (Tazkira-i-Jahangiri), Emperor Jahangir

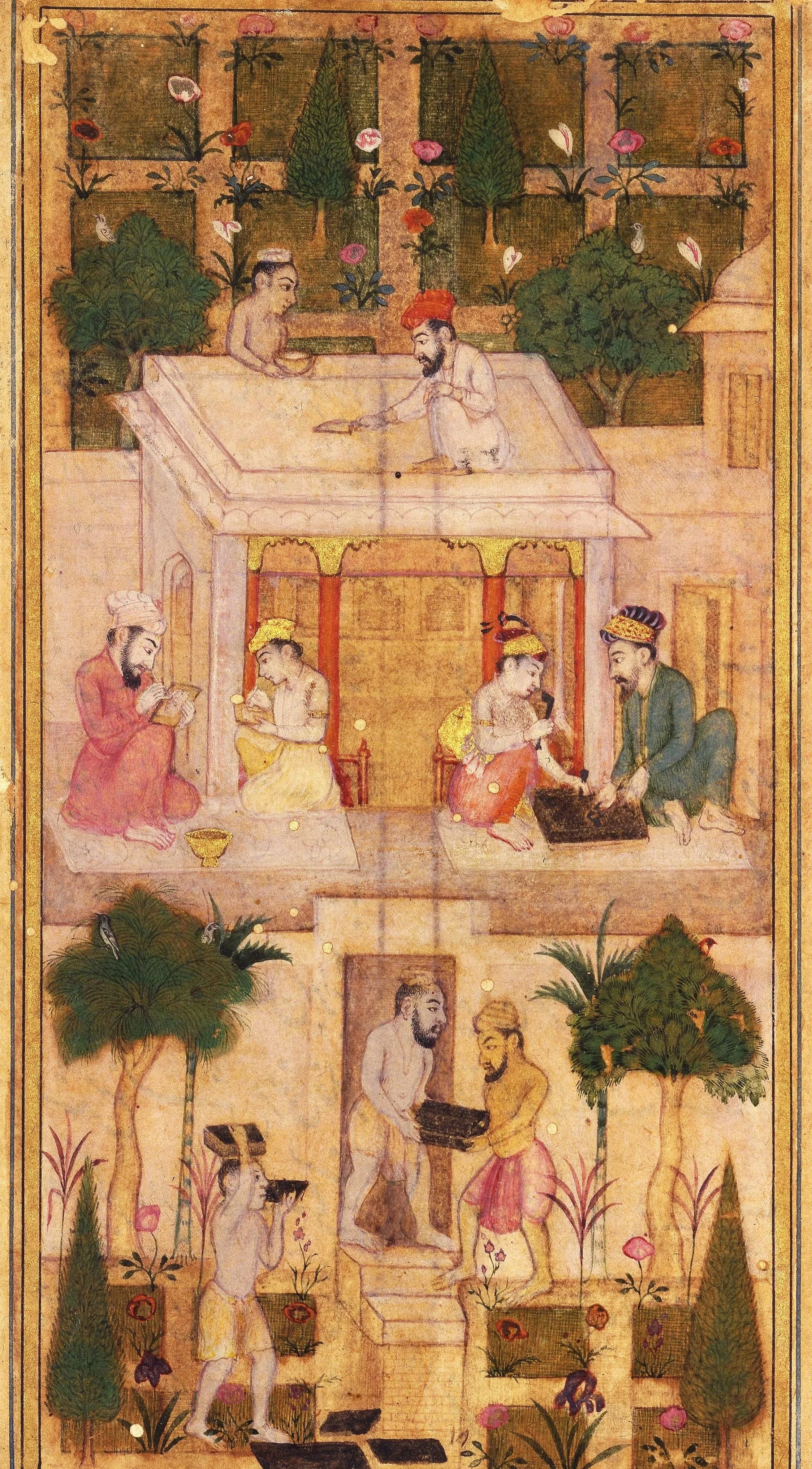

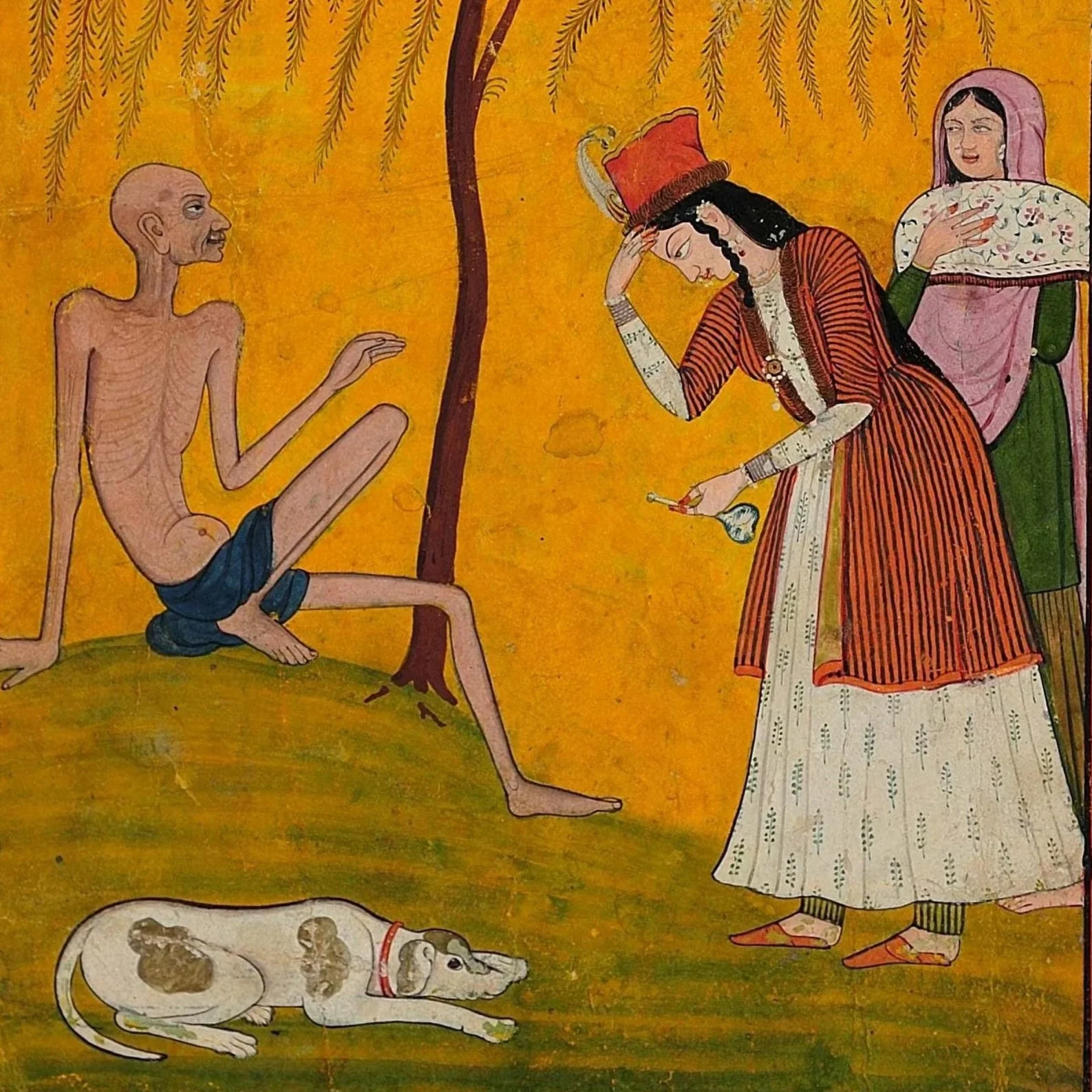

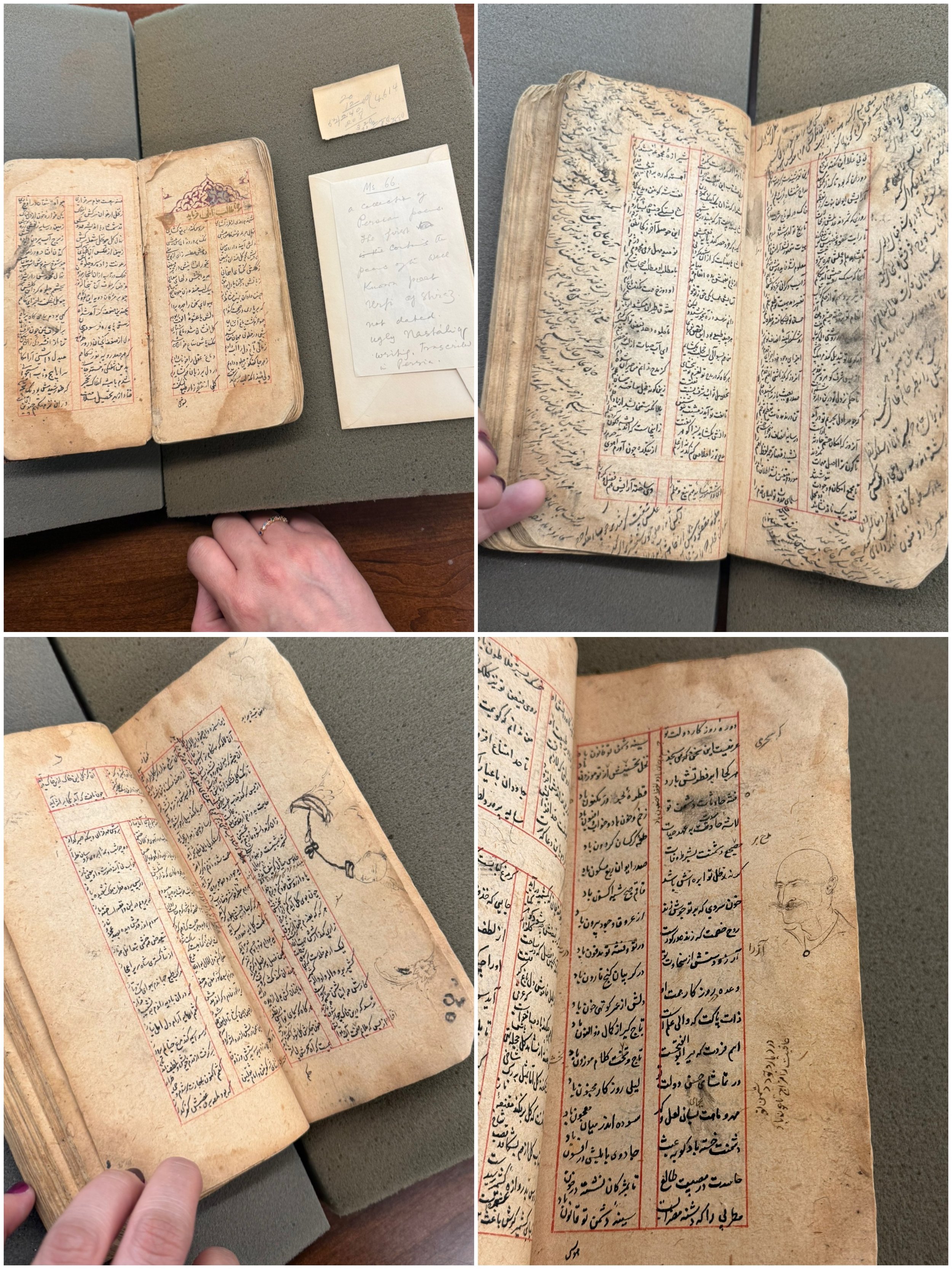

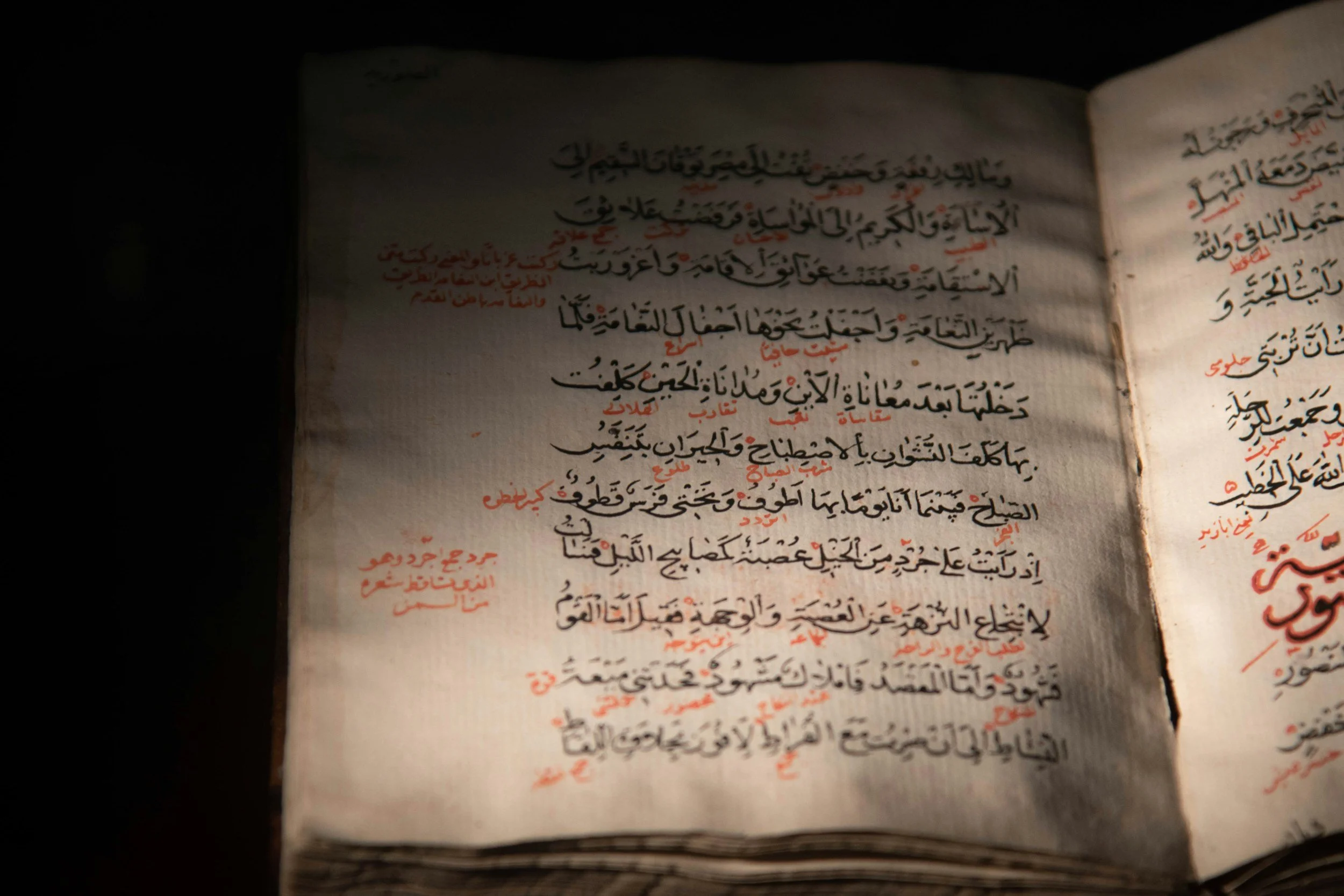

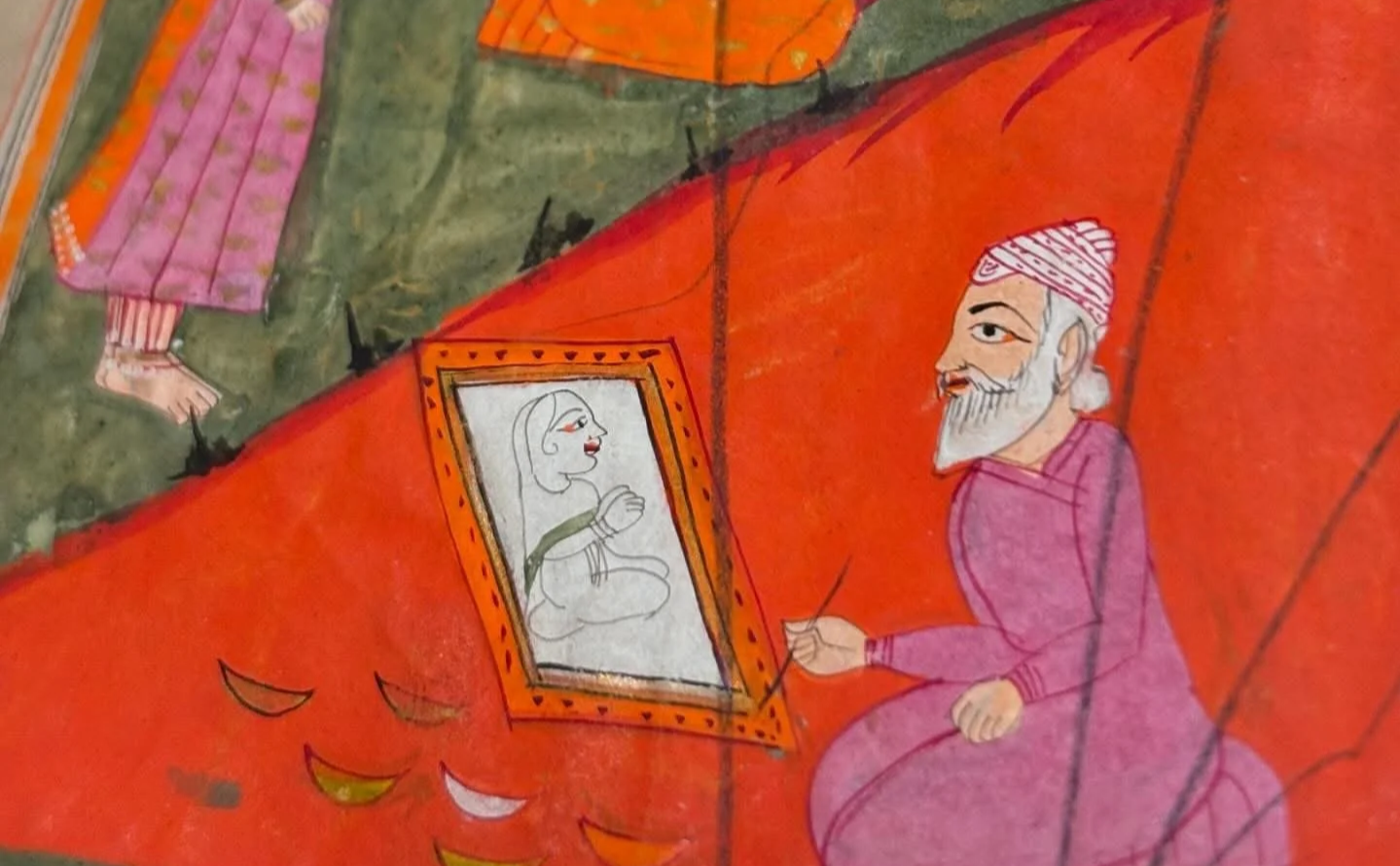

The informal marginal drawings, such as the face of a mustached man and a figure on a noose, neither of which appears to relate directly to the text, were likely added by anonymous later readers rather than the original scribe. For scholars, these seemingly unacademic additions are important because they document how the manuscript was handled, personalized, and emotionally engaged with over time, offering rare insight into the everyday human interactions that shaped the afterlife of Persian literary works beyond their original production. Such marginalia are often interpreted as evidence of reader response, moments of contemplation, boredom, or emotional reaction, and they complicate the idea of manuscripts as fixed or purely authoritative objects. When manuscripts enter libraries or museum collections, these marks become part of the material record, allowing historians to reconstruct patterns of ownership, use, and interpretation that are otherwise absent from formal colophons or textual commentary. In this way, non-textual annotations and drawings contribute to a broader understanding of manuscript culture as a dynamic process in which meaning was continually negotiated by successive readers across time and place.

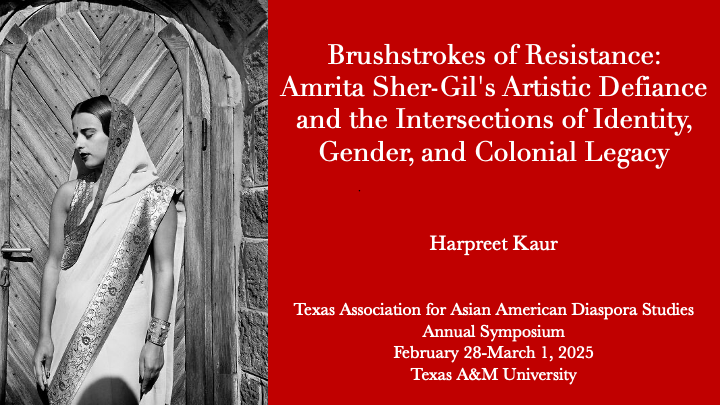

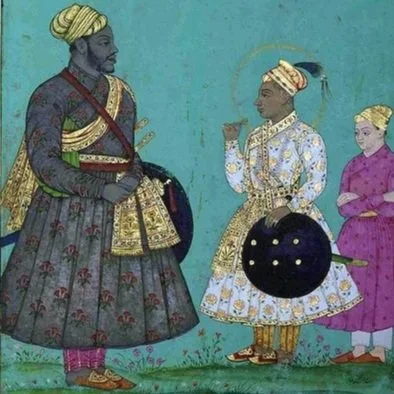

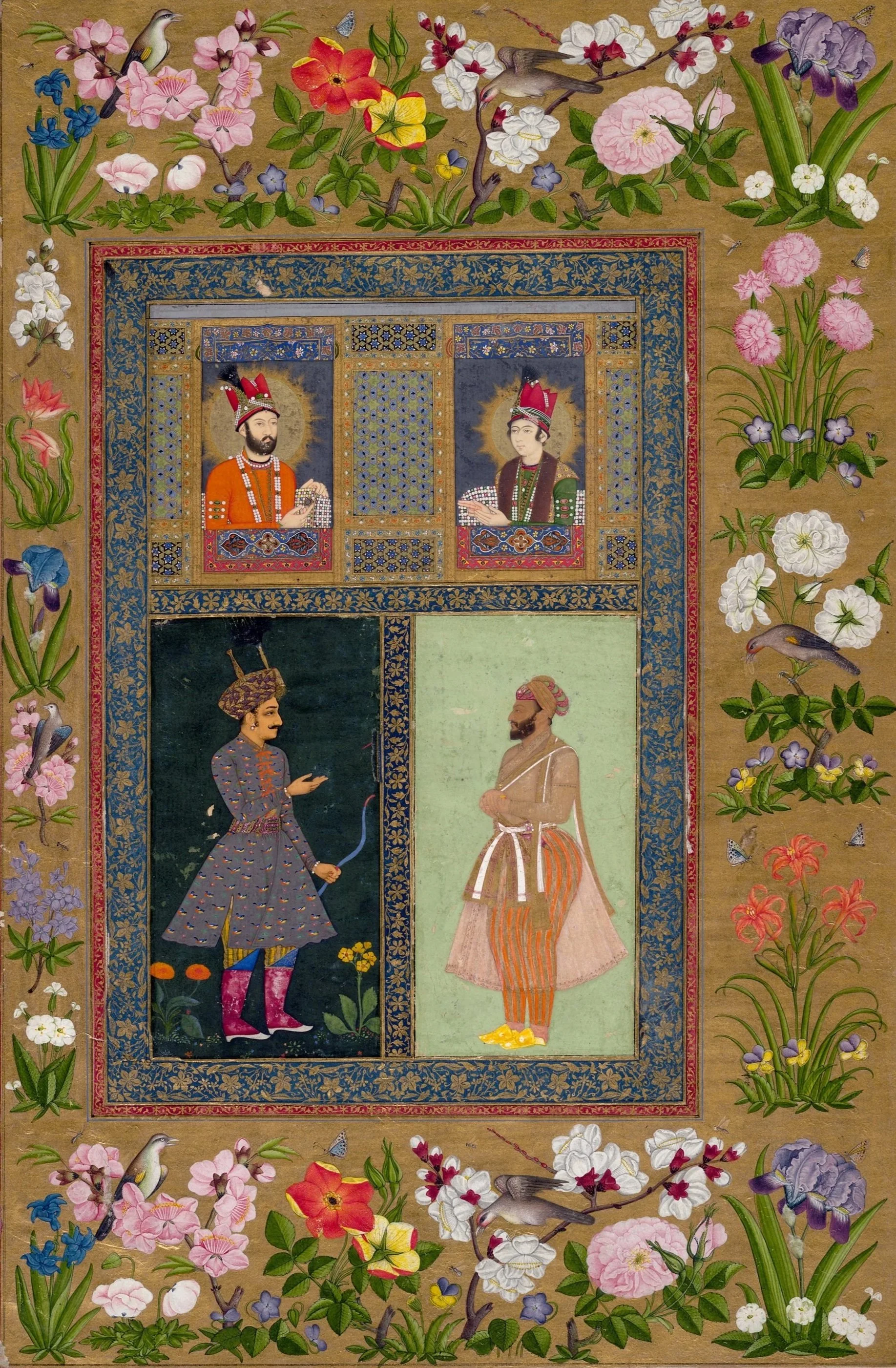

St. Petersburg Mughal Muraqqa: Circulation, Interpretation, and the Transformation of South Asian Visual Culture in Russia

CELEBRATING NOWROZ

The works we leave behind will speak of us.

- Arabic proverb quoted by Shah Jahan's court historian 'Abd al-Hamid Lahori ca. 1642